A Young Artist

Ezra Jack Keats was born on March 11, 1916 in the East New York section of Brooklyn. He was the third child of Benjamin Katz and Augusta “Gussie” Podgainy, Polish Jews who came to this country to escape the aggressive anti-semitism in Europe. Ezra’s mother, as well as his older siblings, William and Mae, were all artistically gifted, but early on it was clear that making art was Ezra’s special gift, as well as joy.

Ezra’s teachers and school librarians gave him the encouragement he needed to believe in his talent. When he graduated from Junior High School 149 he was awarded a medal for drawing and at Thomas Jefferson High School, he won a national Scholastic Award for his painting of a few hobos warming themselves around a fire. These awards also gave him “fuel” to believe in himself and they were still among his treasured possessions when he died.

Ezra’s family had always been poor but during the Great Depression of the 1930s, many, including the Katz family, suffered even greater hardships. Although Ezra’s mother was supportive of his talent, his father worried that Ezra wouldn’t be able to earn a living. Nevertheless, Benjamin, who worked as a waiter, still brought home tubes of paint, pretending he had traded them with penniless artists for food.

Tragically, Benjamin died of a heart attack the day before Ezra’s high school graduation, at which he was to be awarded the senior class medal for excellence in art. Ezra had to identify the body, and in an interview with his friend, the poet Lee Bennett Hopkins, he said: “There in his wallet were worn and tattered newspaper clippings of the notices of the awards I had won. My silent admirer and supplier, he had been torn between his dread of my leading a life of hardship and his real pride in my work.”

Out in the World

Ezra received three art school scholarships after high school, but instead he worked to help support his family and took art classes whenever he could. Among the jobs he held were with the Works Progress Administration (WPA) as a mural painter and at Fawcett Publications, illustrating backgrounds for the Captain Marvel comic strip.

Ezra joined the Army in 1943 and designed camouflage patterns used to help win World War II. In 1947, having experienced severe anti-semitism before, during and after the war, he changed his name to Ezra Jack Keats, to get work as a fine, as well as commercial artist. Experiencing this discrimination is why he understood those who suffered similar hardships.

In 1949, with help from his brother William, Ezra studied painting in Paris and traveled around Europe. Many of the paintings he created in Europe were later exhibited in this country. He continued to paint and exhibit his fine art throughout his life but after returning to New York, he earned a living as a commercial artist. His illustrations appeared in Reader’s Digest, the New York Times Book Review, Collier’s and Playboy, as well as on the jackets of popular books.

It was because Elizabeth Riley, an editorial director at Crowell Publishing, saw one of his covers in a bookstore window, that Ezra was drawn into the world of children’s literature. Riley invited him to illustrate a few picture books for Crowell. The first was Jubilant for Sure, by Elizabeth Hubbard Lansing, published in 1954. In the years that followed, Keats was hired to illustrate many children’s books written by other authors, among them the Danny Dunn adventure series.

The Books

Ezra’s first attempt at writing and illustrating his own children’s book was My Dog is Lost!, co-authored with Pat Cherr and published in 1960. Juanito loses his dog upon arriving in New York City from Puerto Rico. Speaking only Spanish, Juanito searches the city, meeting children from Chinatown, Little Italy and Harlem. Even before The Snowy Day, Ezra wrote about minority children and pioneered bi-lingual picture books.

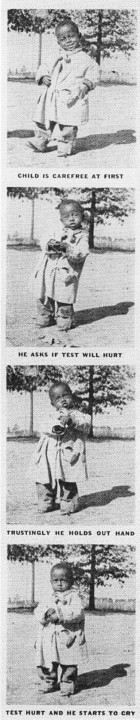

Then, Annis Duff, an editor at Viking Press, invited Ezra to write and illustrate a book of his own. “Then began an experience that turned my life around,” he wrote, “working on a book with a black kid as hero. None of the manuscripts I’d been illustrating featured any black kids—except for token blacks in the background. My book would have him there simply because he should have been there all along.” Ezra’s inspiration for the character of Peter was a group of photographs he had clipped from a 1940 issue of Life magazine depicting a little boy about to get a blood test, “Years before I had cut from a magazine a strip of photos of a little black boy. I often put them on my studio walls before I’d begun to illustrate children’s books. I just loved looking at him. This was the child who would be the hero of my book.” And this book was The Snowy Day.

Published in 1962, The Snowy Day, was awarded the Caldecott Medal in 1963. (Ezra’s Caldecott Acceptance Speech). Ezra described creating The Snowy Day, “I was like a child playing,” “I was in a world with no rules.” Ezra experimented with techniques he had never tried before – combining collage, handmade stamps, and spattering ink – to create the striking illustrations for which The Snowy Day is now famous. Almost twenty books written and illustrated by Ezra followed The Snowy Day, six of which include Peter as he grows from childhood to early adolescence. In subsequent books, like Goggles! and A Letter to Amy, he blended collage with gouache, marbled paper, acrylics, watercolor, pen and ink and even photographs.

Beyond Peter

During the 1960s and ’70s, in addition to writing and illustrating, Ezra taught and traveled extensively. He visited classrooms around the country and corresponded with many children, encouraging them to “Keep on reading!”

The honors he received over the course of his career ran the gamut from his being the first artist invited to design greeting cards for UNICEF (1970), and the first children’s book author invited to donate his papers to Harvard University, to having a roller rink in Japan named in his honor and appearing on Mr. Roger’s Neighborhood four times!

Ezra died in 1983 after suffering a major heart attack during the time he was illustrating and writing his version of The Giant Turnip, a beloved folktale. To this day his books are translated into languages that span the globe and adapted into plays, operas, and major animated movies. The Library of Congress counts The Snowy Day as a book that has shaped America and it is the most checked out book in the 125 year history of the New York Public Library.

Ezra never married or had a family of his own. But he built a family that included the children of his dear friends and the children who let him know how much they loved his books. It was a very big family.